Teasers and the Poetic Function of Language

Teasers have been on my mind and my desk for a few weeks now. So have blurbs. They are both promotional tools for selling books. Perhaps the best promotional tools for selling books. They’re the triggers that entice potential readers to click and buy.

I’ll define a teaser as a one- or two-line hook for a book.

I’ll define a blurb as a 200-word description on the back of a book jacket.

See: Writing Blurbs I

See: Blurb Writing II

Teasers and Roman Jakobson

Roman Jakobson (1896-1982) was a Russian-American linguist. He is well known for having theorized the Six Factors and Six Functions involved in any given linguistic encounter. A schematization of these factors and functions serves as the title image.

Of particular interest in this blog is his understanding of the poetic function of language. As suggested by the schema in the title image, the poetic function corresponds to the message factor.

Jakobson asks the question: What makes a verbal message a work of art? What is it that differentiates a poetic text from a non-poetic text?

He answers: The poetic function of language comes into play when a verbal message focuses on the verbal message itself. It is language that calls attention to language.

Jakobson does not apply his answer exclusively to traditional poetry. For instance, certain clichés – let’s call them the poetry of everyday language – fall within his definition. He offers the example of ‘innocent bystander.’ It is composed of two dactyls: long-short-short, long-short-short. Speakers of English could say ‘random onlooker’ but we don’t. ‘Random onlooker’ has no rhythm. ‘Innocent bystander’ does. So it stuck.

Jakobson also, insightfully, includes political slogans and advertising jingles as examples of the poetic function. And I will now add here – at least, to a certain extent! – a good teaser.

Examples of the Poetic Function

Julius Caesar’s veni, vidi, vici ‘I came, I saw, I conquered’ has echoed down through the ages. He wrote it as a description of the fast and easy victory he had in Asia Minor. Who cares now which battle it refers to? No one. It’s rather that the phrase functions like a phonetic stake in the ground. Caesar’s decisive consonant-vowel economy is the linguistic expression of his military victory. And it is remembered 2000 years later.

Speaking of catchy political phrases, does anyone remember I like Ike? And if you do, do you think it was responsible for Dwight D. Eisenhower’s successful presidential campaign in 1952? I’m tempted to say so, but of course I can’t say that it alone gets all the credit.

However, I can say that hardly a better political slogan exists. The verbal figure ‘Ike’ sits beautifully within ‘Like.’

Speaking of nested verbal figures, you know the long-running Maybelline ad and can likely sing the jingle.

You have two-thirds of the product name twice before you get the full product name. Genius. Also infinitely meme-able, but that’s another story.

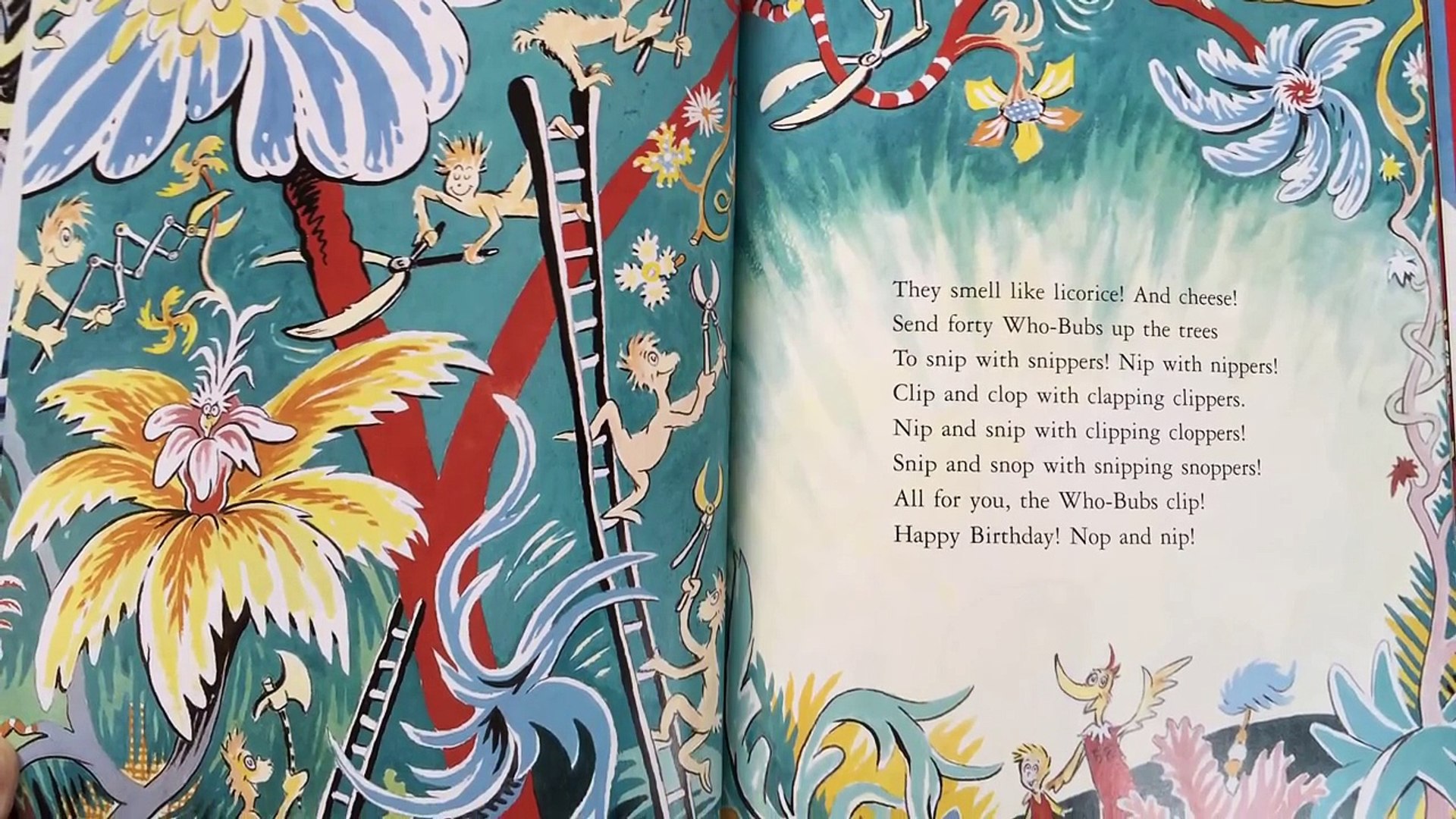

All of Dr. Seuss exemplifies the poetic function of language.

This remarkable passage from Happy Birthday to You! is a phonetic delight. The consonant-cluster alternations have snap. The vowels have the background rhythm of tick tock and end on the surprise reversal: nop nip (tock tick).

Teasers and the Poetic Function of Language

Poetic language is compressed language. Its verbal properties vie for attention with the meaning of the message.

Because a teaser is advertising a specific book, the meaning of the message still needs to come through. Thus a teaser differs from a slogan designed to sell, say, an entire product line: Maybe … Maybe … Maybelline.

I’ll offer a couple of my efforts:

#1

For The Alpha’s Edge, I wrote a 191-word blurb and condensed it into the 8-word teaser:

Werewolves, mating and murder. What’s not to love?

The first three words are trochees (long-short), and the second two words alliterate. Not stunning poetic invention, but it does roll off the tongue.

#2

For Carolina Sonnet, I wrote a 206-word blurb and condensed it into the 16-word teaser:

Nothing could be finer than to be in Carolina on a dewy springtime small town romp.

The first half works – and is clearly not original with me. It’s a series of 7 trochees with an internal semi-rhyme. The last 9 syllables include three trochees and ends on a single-syllable stressed word. So not a perfect match to the first half. But it does have cadence.

Hm.

Okay, no poetic tour de force in either of these teasers. However, I believe that, even if they fall short of an immortal veni-vidi-vici ideal, having a sense of that ideal has helped me to proceed.

For instance, the original second-half of the second teaser for Carolina Sonnet was: “on a springtime scavenger hunt in Hillsborough.” The information conveyed is correct. The story is constructed around a scavenger hunt, and it does take place in Hillsborough, NC. However, as a phrase it falls flat. So I had to come up with something fresher and livelier. Thus “dewy” and “romp” came into the picture, and “small town” swapped out Hillsborough.

Teasers and the Queer Syllogism

When poetic possibilities fail, you might try the style I call a “queer syllogism.”

For Tied Up, I came up with:

Sarah’s tastes are anything but vanilla. Nate is an experienced Dom. They’re on the trail of ruthless child traffickers. What do beautiful silk ties have to do with it?

For The Hard Bargain, there’s:

Billionaire Arthur Wexler needs a faux fiancée. Actor Carla Pereira needs the gig. It’s for one Sunday afternoon only …. What could go wrong?

The form is something like: If hero A. Then heroine B. Throw in plot-point C. Conclusion: What the heck?

For more writing tips, you can view my complete guide on how to write a book.

Categorised in: Blog, Language, Writing, Writing Tips

This post was written by Julie Tetel Andresen

You may also like these stories:

- google+

- comment